With an eye towards female-focused YA speculative fiction, Thea James’s Old and New is a monthly column that examines new and shiny speculative fiction titles, contrasted against an older, foundational (or underrated!) SFF work.

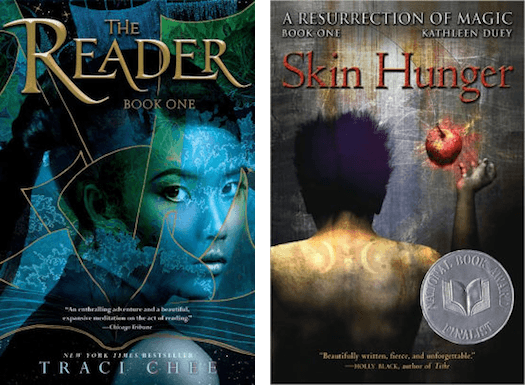

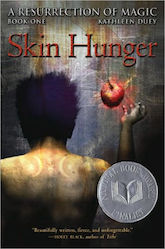

This month’s subjects are two favorites. For the new, there’s Traci Chee’s under-appreciated Reader/Sea of Ink and Gold trilogy (The Reader, The Speaker, The Storyteller). For the old, there’s the sadly unfinished Resurrection of Magic books (Skin Hunger, Sacred Scars) by Kathleen Duey. Both series alternate backwards and forwards in time; both feature a small core cast of main characters including a female character with magical ability who will make decisions that will change their respective worlds. Most importantly, both series meditate on the magic of oral, but especially written, tradition. There is magic in words—Sefia and Sadima know this, and wield that power as best they can.

But I’m getting ahead of myself: let’s start with Traci Chee’s Sea of Ink and Gold trilogy.

In The Reader, we’re introduced to the island kingdom of Kelanna, and a young woman who has lived on the run with her aunt for a very long time. Sefia is a sneak-thief, and a damn good one—though she’s never really understood why her father and mother were murdered, or what secret her Aunt Nin has protected so fiercely for her entire life. When Nin is captured, Sefia is desperate to save her and finally discovers the object that has cost her family everything: a rectangular object, containing loose pages covered with mysterious markings.

Buy the Book

The Reader

This is a book, it says. In Kelanna, a world where reading is not only outlawed but forgotten by its populace, a book is not only precious but magical. Sefia’s book, the only book, is a tome without end—it writes the story of every creature that has ever lived, is living, or will live. For Sefia and Archer, the slave boy she finds and frees, the book holds the promise of adventure, but also of war, vengeance, and death. And as Sefia learns to read the book, she also realizes the true potential of her own magic, and the role she and Archer will play in the chaos to come.

Pursued by the shadowy power organization known as the Guard, its magicians and its assassins, making enemies and allies along the way, the duo embark on an adventure to find answers, revenge, and save the five kingdoms—though their interpretation of what’s best for their world, and their role in shaping it in The Speaker and The Storyteller, pushes them ever further apart.

As a counterpoint to Traci Chee’s Sea of Ink and Gold, there’s Kathleen Duey’s superb Resurrection of Magic books. Comprising two books, Skin Hunger and Sacred Scars, the series remains sadly unfinished (Duey has been diagnosed with acute dementia)—and yet, for all of the open ends and questions, these books are so poignant and remarkable that they should be read. The story is thus: in a time long long ago, a young girl named Sadima is born on a farm. Her mother dies of labor and Sadima is very nearly also killed, victim to an unscrupulous “magician” who steals her family’s money and makes off into the night. Ever since, her father and older brother have been fanatically protective of Sadima—preventing her from going into town and meeting other people. When she starts to manifest strange abilities—the ability to speak to animals and understand their thoughts—her brother and father refuse to believe in her magic. So when Sadima meets someone who does believe her—a gentle-eyed magician named Franklin—she does everything she can to join him and his partner, Somiss, on their quest to revive magic.

Skin Hunger takes place many generations (centuries?) in the future, following a young boy named Hahp, born to a powerful family. Though rich, Hahp’s life is hardly carefree; his father abuses Hahp, his brothers, and especially his mother. One fateful day, his father pulls Hahp away without warning or explanation and deposits him at a school of wizardry. (There never has been a wizard in their family, and Hahp assumes that his father is hoping that Hahp might be the first.) The academy is nothing like he ever could have predicted, though: he learns upon arrival that only one of their class will graduate, where “graduation” is analogous to survival. He and his fellow students are pitted against each other from the very beginning, starved until they can manufacture food by way of magic, and are given no mercy or access to the outside world. One by one, Hahp’s classmates begin to die, and Hahp despairs. The wizards at the academy are no help—Franklin is well-meaning but useless, and Somiss is terrifying—and Hahp fears he will never see sunlight again.

Buy the Book

Skin Hunger

Over the course of Skin Hunger and Sacred Scars, we become intimately familiar with Sadima and Hahp’s storylines, separated by generations though they are. We see—oh so gradually!—how Franklin and Somiss came to power, what Sadima’s role was in the resurrection of magic, and what the repercussions are for their world so many generations later. Unfortunately, there are a ton of open questions and we never get to see the precise intersection of Sadima and Hahp’s storylines—but the parts that we do get to see are brilliant.

When I first started reading The Reader, it felt strangely comforting. Familiar, even, in the way that fantasy novels sometimes can feel, and it took me a while to pinpoint why. Then it hit me: it was similarity of two of the main characters, Sefia and Sadima. Both heroines are orphans of sorts, hungry for answers to the unique magic they each possess. Both heroines care for others, to a fault and potentially calamitous ends—Sefia for her lost aunt and for her newfound friend Archer, Sadima towards Franklin and the work he and Somiss are doing.

There are other character similarities, too: the brutality of both books is unyielding, and the treatment of the male protagonists Archer and Hahp is particularly intense. Though the two boys’ backgrounds are different, the life-or-death, kill-or-be-killed challenges they face are shockingly similar. Unfortunately for Hahp, he doesn’t have a Sefia to help guide him back towards the light in the darkest of hours—but he does have a strange kind of kinship with his roommate, if not the other boys in the Academy. This is perhaps the starkest difference between the two series: The Reader books centralize the power of relationships and their tangled storylines, whereas the Resurrection of Magic series revels in the isolation of each of its main characters.

Beyond the similarity of the main characters, at each story’s core, there’s the importance of words and the magic that writing and understanding language can unlock.

Sadima, a commoner, is prohibited from reading by law—but as she works to copy texts for Somiss and Franklin, she learns their shapes and sounds and meanings. Both characters unlock magic in the very act of this knowledge: Sadima codifies folk songs and common magics while Sefia is able to discern the pattern of strings that tie together time and space. Through the act of reading, both series examine prophecy, history, and memory—spanning multiple generations, and even some timelines. In the case of Skin Hunger and Sacred Scars, Sadima’s determination to learn has less to do with Somiss’s great ambition to resurrect magic (and prove himself to his royal family) than it does with her desire to learn and joy in unlocking the meaning that underlies each of the songs she has worked so hard to record.

This is a book, Sefia writes over and over again after she learns the shape and sound of letters in the illicit tome she carries and protects in The Reader. Sefia learns that her parents have already given her clues as to the magic that lies in text, and as she pours over the impossible stories contained within the book’s never-ending pages, she reads truths about the past and possibilities for the infinite futures ahead.

This is all super meta, of course, and pretty rad when you think about what The Reader entails: a book about a book comprising the stories of everyone within the universe, past/present/future inclusion. In a world where recorded knowledge is unheard of, the person with both the book and the ability to read is the most powerful and fearsome creature to exist. And that, dear readers, is the best thing about books and the act of reading overall—as in both Sefia and Sadima’s worlds, transcribed and shared words are power.

Perhaps these written words will encourage you to give these two fantastic series a try.

Thea James is half of the maniacal book review duo behind The Book Smugglers. By day, she does digital operations things over at Penguin Random House. By night, she watches an abundance of horror movies, stays up far too late editing and reading, and voraciously devours all the SFF. You can find her on Twitter andInstagram @booksmugglers.